Tirow and Håfa adai!

Welcome to the Marianas

The Mariana Islands are an archipelago that includes the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) and Guam. Coral reef ecosystems of the Mariana Islands are essential to the livelihoods of over 200,000 people who call the islands home. The region’s Refaluwasch (Carolinian) and CHamoru (spelled Chamoru in the CNMI) indigenous peoples are linked to Micronesian culture with deep connections to the surrounding seas.

Refaluwasch and CHamoru are the official languages in the Marianas, along with English.

Some local names on this page are in the following format: Refaluwasch/CHamoru (English).

Rising nearly 6 miles from the Mariana Trench, the Mariana Islands are the highest peaks of a vast undersea mountain range in the western Pacific Ocean. [1] There are 14 islands in the CNMI. The northern islands were formed by volcanic activity and still actively erupt, and the southern islands are composed of porous limestone formed by ancient reefs.

Map of the Marianas archipelago

The single island of Guam is a mix of both, with the northern half composed of ancient reef limestone and the southern half shaped by volcanic eruptions.

Sites with vast areas of reefs support large villages such as Litekyan (Ritidian), Tumhon (Tumon), and Malesso (Merizo) in Guam, and Tanapag, Garapan, and San Antonio in Saipan.

Reef Snapshot

256

—Coral species—

400+

Guam

CNMI

42 sq mi

63 sq mi

-Total reef ecosystem area-

11.6%

11.1%

—Percent coral cover—

$63.4 M

$67.0 M

—Annual reef value*—

Benefits of the Reef

Coral reefs in the Marianas hold intrinsic value as a source of livelihood, traditional knowledge, medicine, and cultural stewardship practices for thousands of island residents. Some additional benefits of local reefs include:

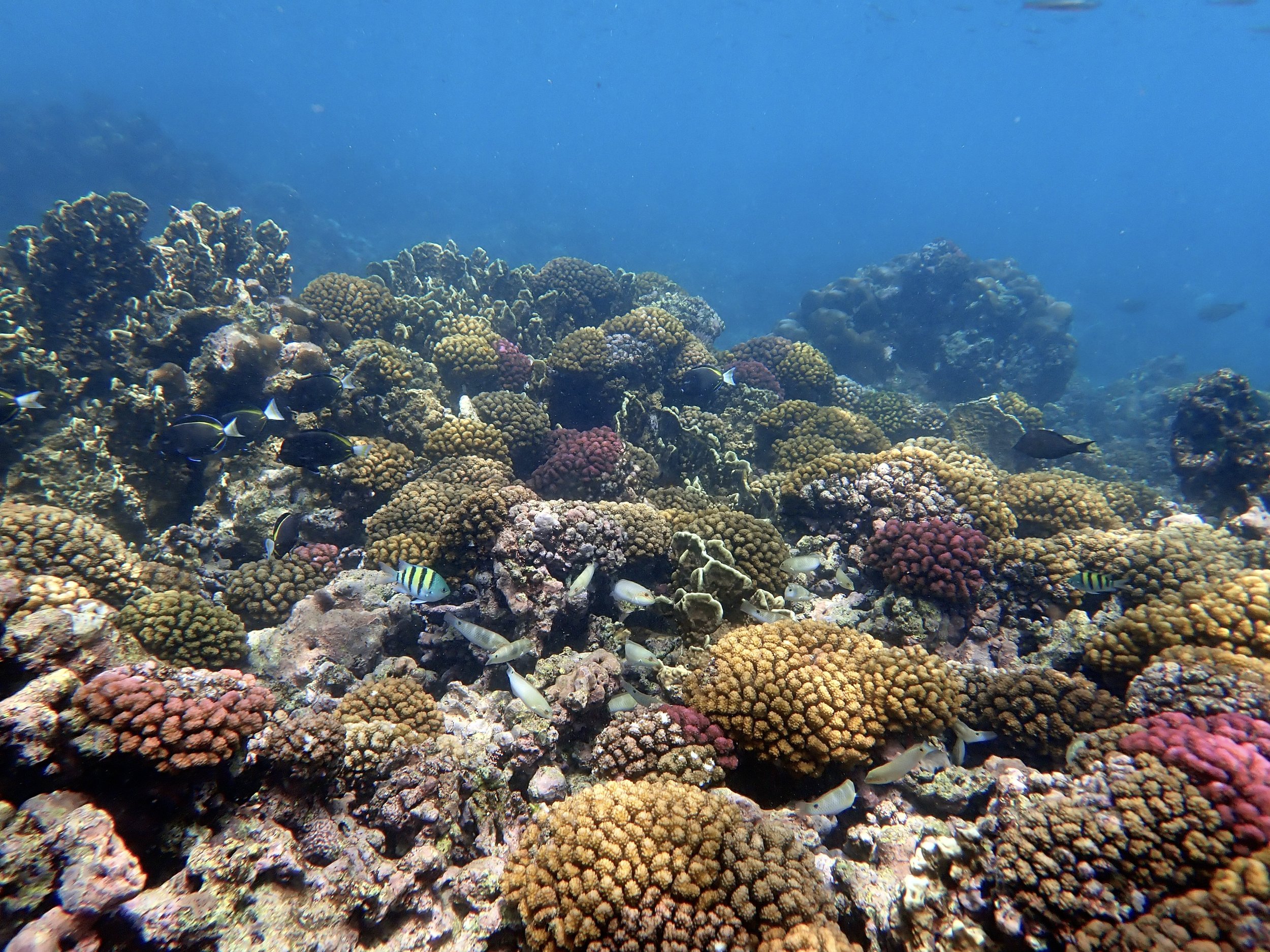

Reef ecosystems support subsistence fishing and provide food and habitat for species such as igh-falafal/tátaga (bluespine unicornfish, Naso unicornis), ighal-wosch/palakse’ (small parrotfish), langú/tarakitu (bluefin trevally, Caranx melampygus), ghúús/gåmson (octopus), ppáleppál/balate’ (sea cucumber), and other seafood that locals enjoy.

Seafood

The Marianas are located in “Typhoon Alley,” a region of the western Pacific where the world’s strongest typhoons occur most frequently. Coral reefs serve as the first line of defense against large, storm-induced waves and flooding, reducing 97% of wave energy. [7] In addition, the reef protects coastal infrastructure from shoreline erosion.

Shoreline protection

-

Each year, reefs in the Marianas prevent an estimated $13.9 million in property damage from coastal flooding. [10]

Tourism

Exploring the reef via scuba diving, snorkeling, underwater observatories, and other activities are major tourist draws in the Marianas.

-

This substantially supports the local tourist economy, which produced an estimated 12,400 jobs and $332.6 M in economic output in 2021 in Guam alone. [11]

Local reefs provide a wide variety of activities and adventures for residents, including snorkeling, stand-up paddling, rowing, SCUBA diving, freediving, and swimming.

Recreation

-

Over 50% of Guam residents participated in swimming/wading and beach recreation in both 2016 and 2023, according to a socioeconomic study conducted by NOAA. [8]

Cultural Significance

Most local myths and legends involve life in the sea, and interisland exchange networks have bonded cultures across Micronesia. Coral reefs are the origins of Indigenous cultures of the Marianas as both CHamoru and Refaluwasch cultures evolved alongside reefs for thousands of years.

The relationship between the CHamoru and Refaluwasch groups goes back to the Metawal wool, an ancient Micronesian trade route that connected the Marianas to the Caroline Islands long before colonization took place.

-

The green fruits displayed on the green leaf in this photo are seeds of the areca palm, also known as betel nuts.

Betelnut chewing, a prominent practice in both CHamoru and Refaluwasch cultures, is partly supplemented by adding slake lime (calcium hydroxide), which is derived from burning specific kinds of coral and grinding it.

This is then combined with pupulu (pepper) leaf (and sometimes tobacco in the modern day) into a betelnut to form the “mix” that is then chewed to give the user a mild calming effect.

Jesuit missionaries recorded this practice during their visits to the islands as far back as the 1600s.

-

This image is an artistic depiction of the legend surrounding the origin of the Santa Marian Kamalen statue, the patron saint of Guam.

In one version of the legend, a fisherman from the southern village of Malesso’/Merizo went spear fishing nearby and spotted a statue of the Virgin Mary on the ocean floor. He dove in to get it, but it retreated and remained just out of reach. He asked the village priest what to do and the priest advised the fisherman to dress in his Sunday clothes and try again. He did so, and this time was able to retrieve the statue.

According to another version of the legend, the fisherman saw the statue in the ocean being carried by two gold-spotted crabs, each bearing a lit candle between their claws. For this reason, Santa Marian Kamelan is also known as the Lady of the Crabs.

(Source: Guampedia)

Art from the Department of CHamoru affairs

“The reef is so much more than a seafood nursery. Tourists come here for the reef and people have a better quality of life because of this resource. Kids come here to play and form core memories playing in these ecosystems.”

— Kalani Reyes, CNMI

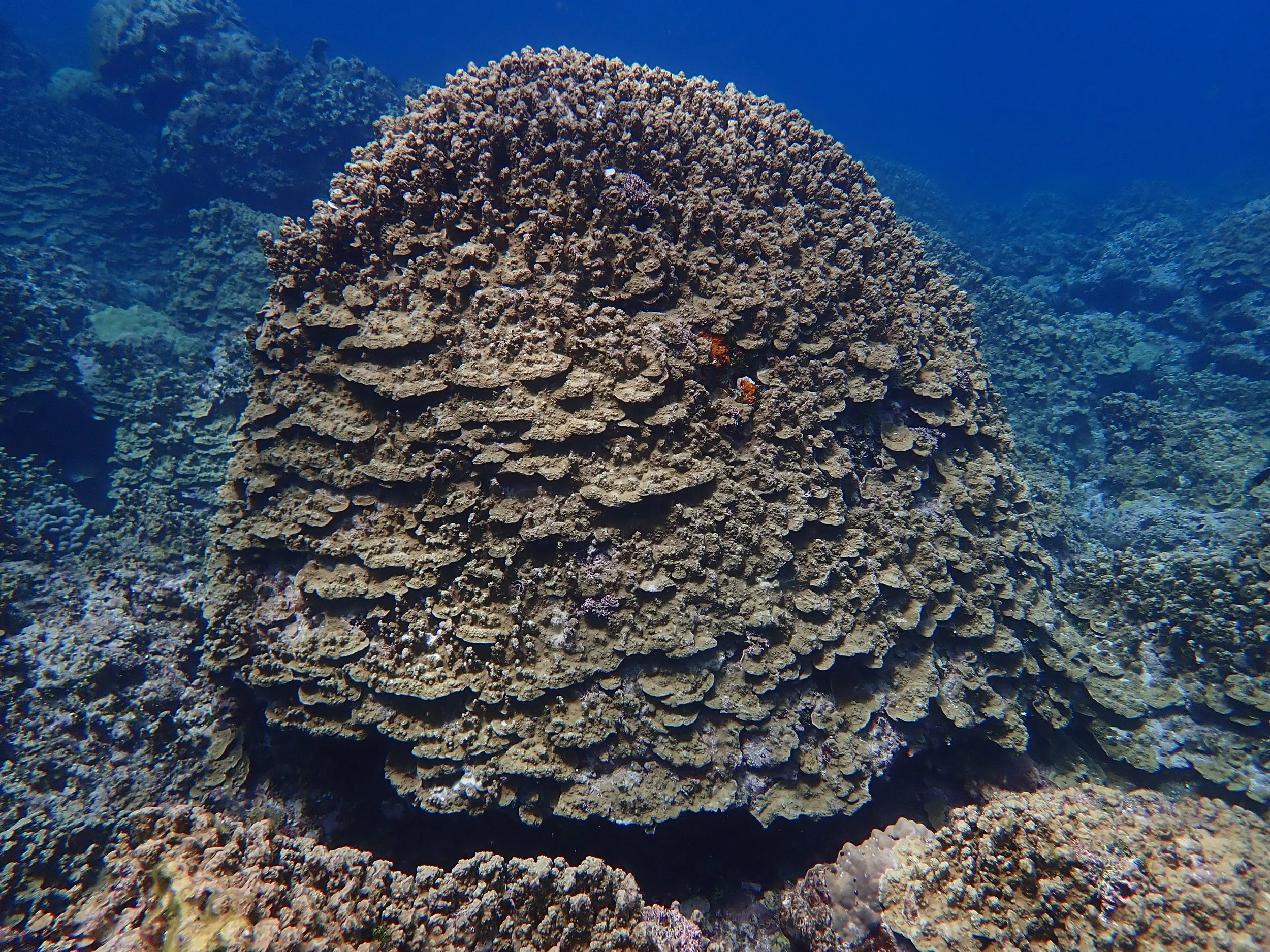

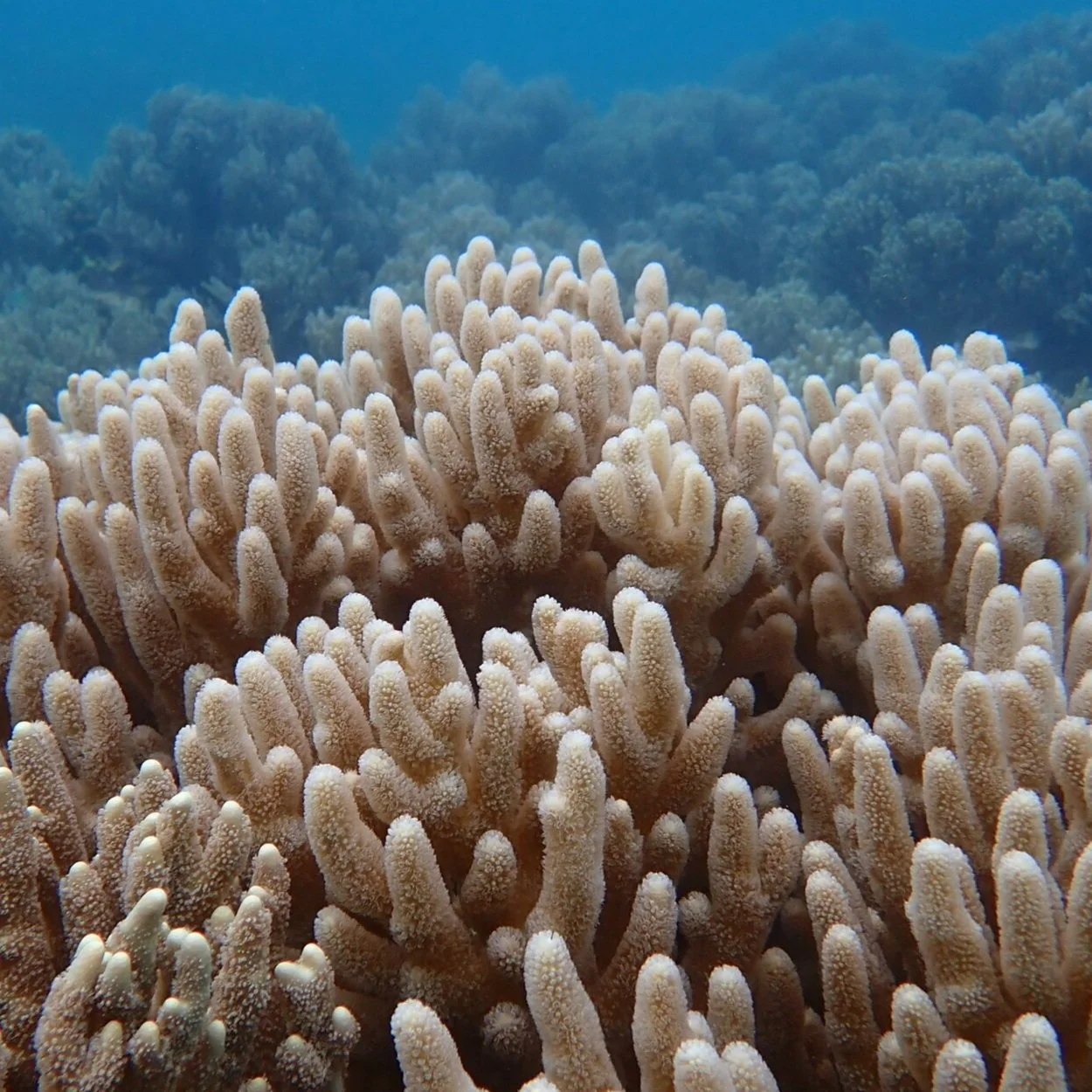

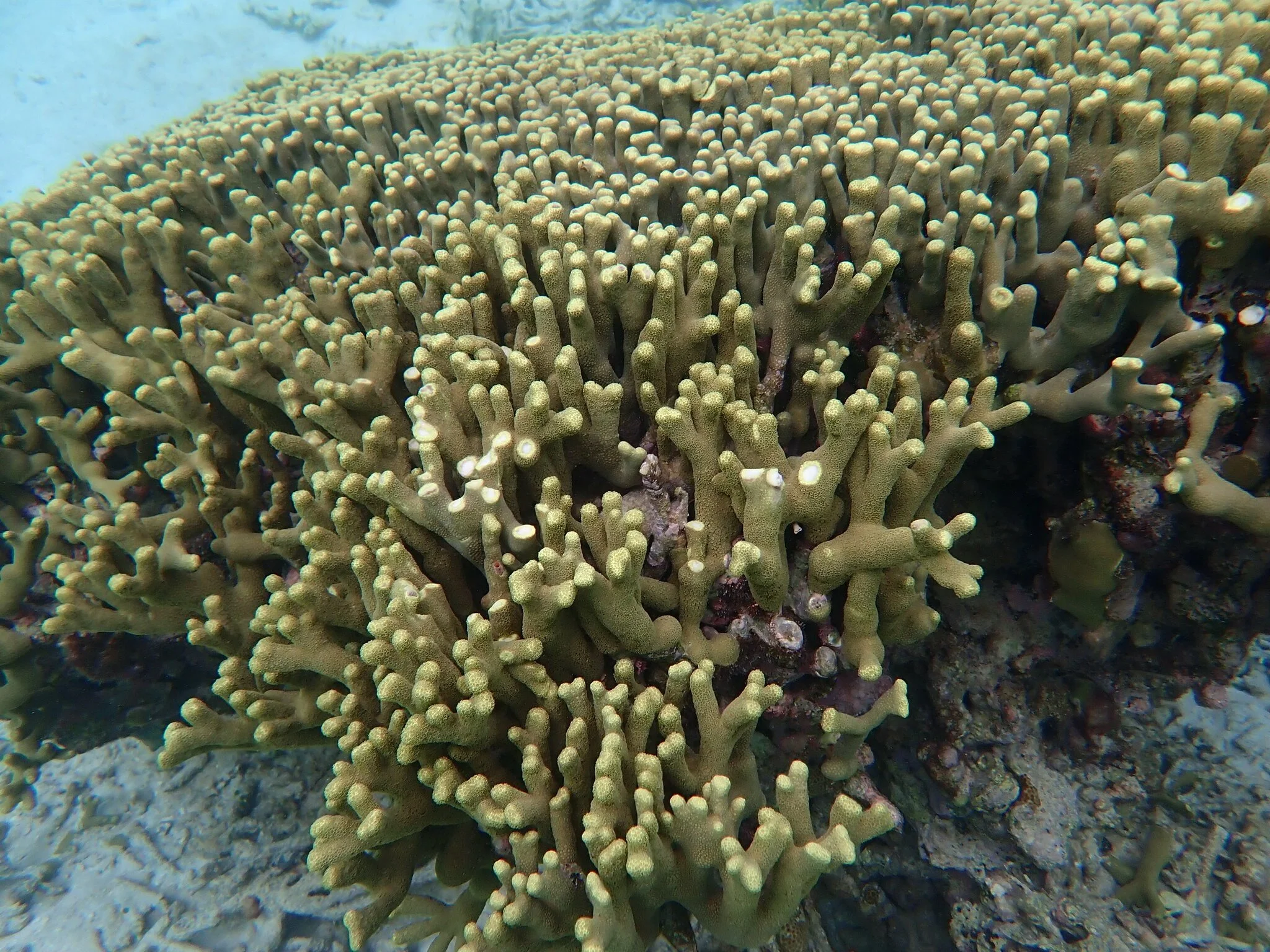

Common corals of the Marianas

Reef Types and Habitats

Situated within the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Mariana Islands were shaped by dynamic geological activity, including frequent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, which fostered the creation of islands and habitats essential for coral reefs. Proximity to the Indo-Pacific region also contributes to the rich biodiversity of marine life.

There are 4 main types of coral reefs: fringing reefs, barrier reefs, atoll reefs, and patch reefs. The Marianas have 3 of these reef types.

Luminao reef, Guam

Fringing Reefs:

reefs that grow right along the coastline.

This is the most common type of reef in the Marianas and is found throughout the CNMI and Guam.

-

In the CNMI, mainly Saipan and Tinian, the fringing reefs are predominantly spur-and-groove and high-relief reef types.

Rota, on the other hand, is predominately a low-relief reef type that is unique because of its raised Holocene reefs. In Rota specifically, these raised reefs are a result of tectonic uplift coupled with a slight sea-level drop during the late Holocene period creating the emergence of Holocene reef terraces. [12]

Saipan Lagoon. Photo: CNMI DCRM

Barrier Reefs:

reefs further from the coastline with a deep sandy lagoon between the shore and the reef.

Saipan Lagoon in the CNMI and Cocos Lagoon in Guam are the only barrier reefs in the Marianas.

-

Saipan is unique in that a barrier reef is formed on the western side of the island, creating a type of lagoon. These lagoons serve as crucial ecosystems, supporting diverse assemblages of corals and seagrasses.

Mañagaha island, CNMI. Photo: CNMI MVA

Patch Reefs:

isolated outcroppings of reefs that tend to grow in shallow lagoons.

In Guam, patch reefs exist throughout the island including in Apra Harbor. Patch reefs can also be found throughout the CNMI, including the areas around Taga Beach and Mañagaha Island.

Other reef-adjacent habitats

In the CNMI, adjacent reef habitats include seagrasses and mangrove ecosystems. Existing mangrove forests are limited to the island of Saipan, where they span approximately 2 acres near the American Memorial Park, adjacent to coral reefs. [13]

Guam also has 180+ acres of mangrove forest and 450+ acres of seagrass meadows adjacent to its reefs, with nearly all mangrove and seagrass habitats occurring in the southern region of Guam. [13]

A pufferfish in Saipan’s seagrass meadows

Mangrove forests in Sasa Bay, Guam

In addition to the relatively shallow coral reefs surrounding the islands, deep-sea corals can also be found in the waters surrounding the CNMI and Guam. Deep-sea corals grow at least 50 meters (164 ft) under the ocean surface but often can be found at depths of several hundred meters.

More than 100 species of deep-sea corals have been documented so far in the Mariana Trench Marine National Monument and surrounding waters off the coasts of the CNMI and Guam. [18]

Deep sea coral photos are from the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research 2016 Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas

Reef Threats

Human-caused climate change is causing increased sea surface temperatures, sea level rise, ocean acidification, and increased extreme weather events; all of which threaten reefs in the Marianas. In addition to these global threats, reefs in the Marianas face significant local threats as well.

-

Harmful soil erosion and sediment runoff are caused by poor erosion control during construction, as well as deforestation from frequent wildfires and invasive species. Increased development from growing populations has also caused polluted stormwater runoff and nutrient discharges from water purification systems.

For example, up until the early 2000s, drinking water purification systems in the CNMI consistently discharged nitrates and phosphates into the Saipan Lagoon, causing harmful algal blooms and other reef issues related to nutrient inflow. [14]

Photo by the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council

-

Overfishing disrupts the balance of coral reef ecosystems by reducing the number of herbivores critical for controlling algae overgrowth. In the Marianas, desirable herbivorous fish such as oscha/låggua (steephead parrotfish, Chlorurus microrhinos), limell/kichu (convict tang, Acanthurus triostegus), and llegh/hiteng kåhlao (forktail rabbitfish, Siganus argenteus) can see steep population declines.

-

Environmental changes can cause some native species to reproduce in large numbers, upsetting an ecosystem's balance. In the Marianas, nuisance species that prey on corals and harm reefs include crown-of-thorns sea stars, Drupella snails, and Terpios sponges. Maintaining their natural predators is crucial to preventing outbreaks of these species and protecting the reefs.

Saipan’s recovery from bleaching in 2013, 2014, and 2017 has been further hampered by ongoing outbreaks of crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS), with densities reaching 48 times higher than the average recorded over the past twenty years. [15]

-

Because tourists come from all over the world to the Marianas, it can be challenging to communicate reef-safe behaviors due to language barriers. As a result, stepping on and vandalizing corals, feeding wild fish, harassing reef species that provide essential ecosystem services, and using non-reef-safe sunblock have contributed to reef degradation.

Restoration Activities

The CNMI has 2 active coral restoration nurseries, both of which are in the Saipan West Lagoon

Photo by Ashley Castro

Johnston Applied Marine Sciences (JAMS) Nursery

Est. 2019

23 coral trees and 4 tables

11 coral species

-

Established with funding from NOAA

One of the species grown in this nursery is endangered species, Acropora globiceps

Donor colonies were survivors of severe bleaching and mortality in 2017 and, therefore, demonstrated resilience to heat stress.

CNMI Government Nursery

Est. 2021

6 coral trees, 2 tables, and 1 rope nursery

11 coral species

-

Established with funds from the U.S. Department of Interior

Managed by the CNMI marine monitoring team, a multiagency group of the CNMI government with other local partners contributing

Currently houses 300+ coral fragments

Guam has 4 active coral nurseries spread across the island

University of Guam Marine Lab (UOG ML) nurseries

Piti Bomb Holes Nursery

Est. 2014

11 coral trees, 4 tables, and 1 rope nursery

8 coral species

Photo by Ashley Castro

Cocos Island Lagoon Nursery

Est. 2019

11 coral trees and 1 rope nursery

8 coral species

-

These nurseries combined have resulted in 4257 coral colonies outplanted and 3.2 acres of reef restored

All corals in the UOG ML nurseries are different species of staghorn corals (Genus Acropora)

The Piti Bomb Holes nursery houses 1689 fragments

The Cocos Island Lagoon nursery houses ~1500 coral fragments

Guam Coral Reef Initiative (GCRI) Piti Bomb Holes Nursery

Est. 2024

6 coral trees

6 coral species

-

Established with funds from the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation

Currently houses 1200+ coral fragments

Photo coming soon

National Park Service (NPS) War in the Pacific National Park Nursery

Est. 2024

2 coral trees (more underway)

-

When this nursery is fully built out, it is expected to have 12 coral trees

Reef Protections

-

Sasanhaya Bay Fish Reserve (est. 1994) on Rota

Mañagaha Marine Conservation Area (est. 2000) on Saipan

Bird Island Sanctuary (est. 2001) on Saipan

Forbidden Island Sanctuary (est. 2001) on Saipan.

-

LaolaoBay Sea Cucumber Sanctuary in Saipan (est. 1996) - bans sea cucumber harvest

Lighthouse Reef Trochus Sanctuary in Saipan (est. 1996) - bans trochus harvest.

-

The CNMI Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) Enforcement Section enforces these marine preserves

The CNMI is home to 6 locally managed marine preserves, 5 of which are on Saipan and 1 of which is on Rota.

-

The CNMI also passed the Coral Reef Protection Act of 2018 (PL 20-79) to protect coral reefs from vessel groundings through the recovery of monetary damages.

Although this law will be implemented once regulations are established, the DFW’s Enforcement Section’s Conservation Officers have received training from the Coral Reef Restoration Coordinator in preparation for the law to come into effect.

Guam is home to 5 locally-managed marine preserves covering over 10% of the island’s coastline.

-

Sasa Bay Marine Preserve (est. 1997)

-

Piti Bomb Holes Marine Preserve (est. 1997)

No fishing, harvesting, or collecting of anything is allowed, except with a seasonal permit for certain species (i.e. atulai, mañåhak, and achemson). Trolling is allowed from the reef margin out to sea for pelagic fish.

Tumon Bay Marine Preserve (est. 1997)

Hook & line and cast net (talaya) ONLY allowed from shore for mañåhak, sesyon, kichu, ti’ao, and i’e. Cast net ONLY allowed from the reef edge for sesyon and kichu.

Achang Reef Flat Marine Preserve (est. 1997)

No fishing, harvesting, or collecting of anything is allowed, except with a seasonal permit for certain species (i.e. atulai, mañåhak, and achemson). Trolling is allowed from the reef margin out to sea for pelagic fish.

Pati Point Marine Preserve (est. 1997)

Hook & line ONLY allowed from shore. Trolling is allowed from the reef margin out to sea for pelagic fish.

-

Each preserve is enforced by the Guam Department of Agriculture Conservation Officers

For all of Guam's marine preserves, the following additional rules apply:

No harming or chasing marine life

No taking sea cucumbers, crabs, snails, coral (alive or dead), or other marine life

No taking sand, shells, rocks, seagrass, mangroves, or other natural materials

Guam also has 4 federally managed marine preserves with differing levels of access and fishing regulations.

-

In addition to marine preserve laws, Guam’s reef ecosystems are also protected by reef-related legislation including:

Public Law (PL) 16-039.6 of 1981 outlawing take of corals growing in 60 ft of water or less island-wide

PL 35-78 of 2020 outlawing SCUBA spearfishing

Resolution No.207-37 of 2024 designating coral reefs as essential infrastructure protecting the coasts of Guam.

This website page and brochure were created by members of the Communications Working Group of the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force representing the following organizations

All photos on this page are by GCRI staff or Communications Working Group members unless otherwise specified

Reefs of the Marianas Photo Gallery

Sources

[1] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (1998, July 20). Mariana Islands. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Mariana-Islands

[2] About the CNMI Coral Reef Initiative. (2018). Division of Coastal Resources Management. https://dcrm.gov.mp/our-programs/coral-reef-initiative/about-the-coral-reef-initiative/

[3] Porter, V., Leberer, T., Gawel, M., Gutierrez, J., Burdick, D., Torres, V., & Lujan, E. (2005). Status of the Coral Reef Ecosystems of Guam Bureau of Statistics and Plans, Guam Coastal Management Program. In Marine Laboratory | Technical Reports. University of Guam Marine Laboratory. https://www.uog.edu/_resources/files/ml/technical_reports/113Porter_et_al_2005_UOGMLTechReport113.pdf

[4] NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program. (2009). Coral Reef Habitat Assessment for U.S. Marine Protected Areas: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. In NOAA CORIS. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.coris.noaa.gov/activities/habitat_assessment/cnmi.pdf

[5] Burdick, D. R., Brown, V., Asher, J., Gawel, M., Goldman, L., Hall, A., Kenyon, J., Leberer, T., Lundblad, E., McIlwain, J., Miller, J., Minton, D., Nadon, M., Pioppi, N., Raymundo, L., Richards, B., Schroeder, R., Schupp, P., Smith, E., & Zgliczynski, B. (2008). The State of the Coral Reef Ecosystems of Guam. ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.2183.8960

[6] National Coral Reef Monitoring Program Pacific Benthic Dashboard

For the CNMI statistics, the following options were selected to produce the data. Jurisdiction: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Geographic Tier: Jurisdiction. Area of Interest: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Year: 2017. Taxonomic Group: ALL RECORDED CORALS.

For the Guam statistics, the following options were selected to produce the data. Jurisdiction: Guam. Geographic Tier: Jurisdiction. Area of Interest: Guam. Year: 2017. Taxonomic group: ALL RECORDED CORALS.

[7] Storlazzi, C.D., Reguero, B.G., Cole, A.D., Lowe, E., Shope, J.B., Gibbs, A.E., Nickel, B.A., McCall, R.T., van Dongeren, A.R., and Beck, M.W., 2019, Rigorously valuing the role of U.S. coral reefs in coastal hazard risk reduction: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2019–1027, 42 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20191027.

[8] M.E. Allen, C.S. Fleming, A. Alva, S.B. Gonyo, and E.K. Towle. 2024. National Coral Reef Monitoring Program Socioeconomic Monitoring Component: Summary Findings for Guam, 2023. U.S. Dep. Commerce, NOAA Tech. Memo., NOAA-TM-NOS-CRCP-51, 44p. + Appendices. https://doi.org/10.25923/819v-4s49

[9] Fries, A., Donovan, C., & Kelsey, H. (2018, December 19). Coral reef condition: A status report for the Northern Mariana Islands. University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science Integration and Application Network; NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program. https://ian.umces.edu/publications/coral-reef-condition-a-status-report-for-the-northern-mariana-islands/

[10] Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center. (n.d.). The value of US coral reefs for risk reduction - Guam and CNMI | U.S. Geological Survey. USGS. Retrieved October 10, 2024, from https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/value-us-coral-reefs-risk-reduction-guam-and-cnmi

[11] Ocean Associates, Incorporated, & Eastern Research Group, Inc. (2023). Comprehensive Report Ecosystem Services Valuation of Guam and Florida Coral Reefs Written under contract for the. NOAA Office for Coastal Management. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/637c51ca2f1cc50767846ba6/t/657be55970df15697699ae5d/1702618459988/Corals+ESV_OY1_Final+Report_Guam+Florida+04-14-23.pdf

[12] Houk, Peter, and Robert van Woesik. “Coral Assemblages and Reef Growth in the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (Western Pacific Ocean).” Marine Ecology, vol. 31, no. 2, 13 Apr. 2010. Wiley Online Library, onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1439-0485.2009.00301.x, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0485.2009.00301.x. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

[13] Plentovich, S., Mizerek, T., Reeves, M. K., Amidon, F., Miller, S. E., & Nanbara, M. (2020). Coastal Strand and Mangrove Swamps of the Mariana Islands. Encyclopedia of the World’s Biomes, 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-409548-9.12422-4

[14] Sridhar, Nikita, et al. “Saipan Coral Nursery Pilot Project.” Saipan Coral Nursery Pilot Project, Esri, 5 Aug. 2020, storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/e3b7072d13ad4f9a80853641e4b2f4e2. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

[15] Perez, D.I.; Camacho, R.; Hasegawa, K.; Iguel, J.; Suel, J.; David, P. CNMI State of the Reef Report 2020 – 2021; Saipan, CNMI Division of Coastal Resources Management, 2021

[16] Raymundo, L. J., et al. “Successive Bleaching Events Cause Mass Coral Mortality in Guam, Micronesia.” Coral Reefs, vol. 38, no. 4, 25 June 2019, pp. 677–700, www.uog.edu/_resources/files/ml/raymundolab/peer-reviewed/Raymundoetal.2019.CORE.successive.bleaching.pdf, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00338-019-01836-2. Accessed 10 Oct. 2024.

[17] Maynard, J., McKagan, S., Johnson, S., Fenner, L. J., Fenner, D., & Tracey, D. (2019). Assessing resistance and recovery in CNMI during and following a bleaching and typhoon event to identify and prioritize resilience drivers and action options. Reef Resilience Network.

[18] Kelley C, Hourigan TF, Bingo, S., Putts, M., Moriwake, V., Cairns SD (2022) Preliminary List of Deep-Sea Coral Taxa in the U.S. Mariana Archipelago (v. 2021) Depth and Geographic Distribution. Online Supplement to The state of deep-sea coral and sponge ecosystems of the United States: https://doi.org/10.25923/wj31-g055