Guam’s Coral Reefs

Coral Basics

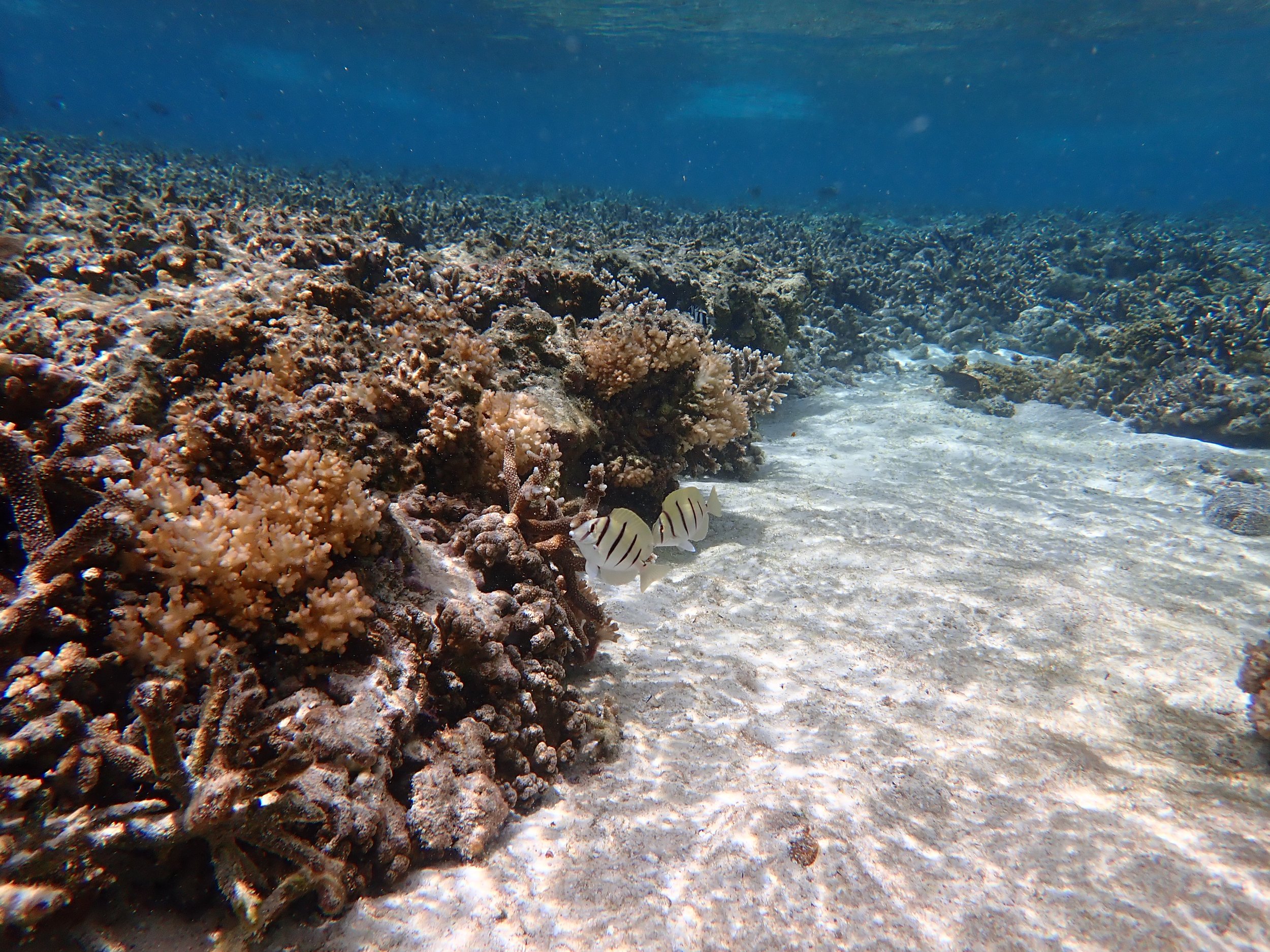

Photo by Dave Burdick

-

Coral is actually an animal!

It is a close cousin to jellyfish and sea anemones, which all belong to the phylum (or grouping of animals) called cnidarians. Each coral structure that you see is actually one big colony made up of tons of individuals, called polyps, that clone themselves over and over again.

Polyps (the tiny sea anemone-looking things in the photo on the right) all work together to make a strong structure that they can take shelter in and grow on top of. This structure is made out of calcium carbonate and is called the coral skeleton. There are many different species of corals, so they come in all shapes and sizes.

-

Because of the algae that live inside of it.

Coral is colorful because of a unique relationship, or symbiosis, with a type of algae. This alga is called zooxanthellae and it actually lives under the skin of coral polyps. Zooxanthellae do photosynthesis and convert carbon dioxide (CO2) into sugars using energy from the sunlight. The coral polyps benefit from these sugars and offer zooxanthellae ample access to sunlight and shelter in return.

Zooxanthellae alone give coral polyps a greenish-brown color. Some corals are a lot more colorful than just greenish-brown, though, and that is because they have pigments: molecules that can absorb certain types of light and reflect others. These pigments mainly act as a sort of ‘sunscreen’ for the zooxanthellae to prevent them from getting overexposed to the bright sunlight, but the side effect is that they make the corals appear bright and colorful.

The more pigments that a coral polyp has, the happier (and less sunburned) its zooxanthellae will be. The happier the zooxanthellae, the happier the coral so these bright colors really are in everyone's best interest!

-

Very slowly!

Coral polyps start as tiny, free-swimming larvae, called planula, and will swim around looking for a flat, rocky surface to settle down on. Once they find a good spot, they permanently attach themselves to this surface and then begin to grow into what looks like a tiny sea anemone. Then, they begin to make their coral skeleton by secreting a white chalky mineral called calcium carbonate. How they actually secrete this chemical is still a subject of current research, but they start with secreting a small amount, just to make a small cup around the base of their body. Over time, the polyp will push away from the base of the cup and then fill in the gaps with new layers of calcium carbonate. As the coral polyp gets bigger, so too does its calcium carbonate cup structure. Eventually, the polyp will clone itself, splitting into two individuals in a process called budding. This repeats over and over again, and eventually all these coral polyp clones form an entire coral colony with a strong calcium carbonate skeleton supporting them all!

-

Coral reefs can be found around the world in warm, tropical, salty waters.

Specifically, coral grows best in water that is between 73 and 84 degrees Fahrenheit. Each coral species has its own range of temperatures that it can tolerate, but generally 64 degrees Fahrenheit is the coldest temperature that corals can survive, and 104 degrees Fahrenheit is the hottest temperature that corals can survive, although only for short periods of time. Coral also grows best in water that is clear, shallow, and sunlit because the algae that lives in their skin (learn more about this algae, Zooxanthellae, in the “Why is coral so colorful?” tab above) needs ample access to sunlight in order to do photosynthesis and provide the coral polyps with the sugars they need.

In the United States of America, coral reefs can be found in territories; Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands; and states; Hawai’i, and Florida.

-

It’s when the algae that normally give coral its color disappear due to stressful conditions

More specifically, coral bleaching is what happens when coral loses its symbiotic zooxanthellae and dies, leaving behind only its white coral skeleton. You can learn more about the relationship between coral and zooxanthellae in the “Why is coral so colorful?” tab above. Coral bleaching happens when corals undergo extreme environmental stress that affects the symbiotic relationship between coral polyps and their zooxanthellae. For example, when the water gets very cloudy from pollution or sediment runoff, zooxanthellae are unable to access the sunlight that they need to do photosynthesis and make sugars for the coral polyps. Coral polyps depend on these sugars for energy, so when the zooxanthellae can’t provide this, the polyps will actually expel the zooxanthellae from their skin. Without zooxanthellae, polyps can survive for a short while but will eventually die, leaving behind only the white chalky calcium carbonate skeleton that the polyps formed and lived on.

Environmental stressors that can cause coral bleaching include pollution and sediment runoff clouding the waters, extremely warm ocean temperatures for prolonged periods of time, extreme low tides exposing corals to the air and drying them out, coral diseases, and other extreme environmental changes.

Scroll down for more information on coral bleaching!

Did you know?

Coral reefs are the most diverse habitats on Earth!

1%

They take up only

of the ocean

Yet are home to

of all ocean species

25%

Why are coral reefs important?

-

Fish and Seafood

Coral reefs provide essential habitats for all kinds of creatures, many of which are important food sources for us humans! Local favorites like tataga (bluespine unicornfish), palakse’/laggua (parrotfish) and gåmson (octopus) all make their home on the reef and wouldn’t be here without it.

-

Coastal Protection

Have you ever wondered why the waves crash so far away from the shore on some parts of the island? It is because of coral reefs! Coral reefs absorb the power of these waves, reducing them to barely a ripple by the time they reach the shore. This prevents erosion and protects homes and businesses along the coast from damage caused by powerful waves.

-

Social and Cultural Activities

The coral reefs supply an endless source of adventure and enjoyment for locals and visitors alike. Snorkeling, scuba diving, stand-up paddling, swimming, and rowing are some of the many activities enjoyed on the reefs here in Guam. Reefs also support traditional fishing practices and other CHamoru cultural traditions. Photo by Kylie Hasegawa

Map of Guam’s Reefs

Guam’s coastal waters host approximately 42 square miles of shallow coral reefs, and 43 square miles of deeper coral reefs at least 3 nautical miles offshore.

Did you know?

Guam’s coral reefs are among the most diverse reefs in the U.S! They are home to…

400

stony coral species

5,100

reef species

1,000

nearshore fish species

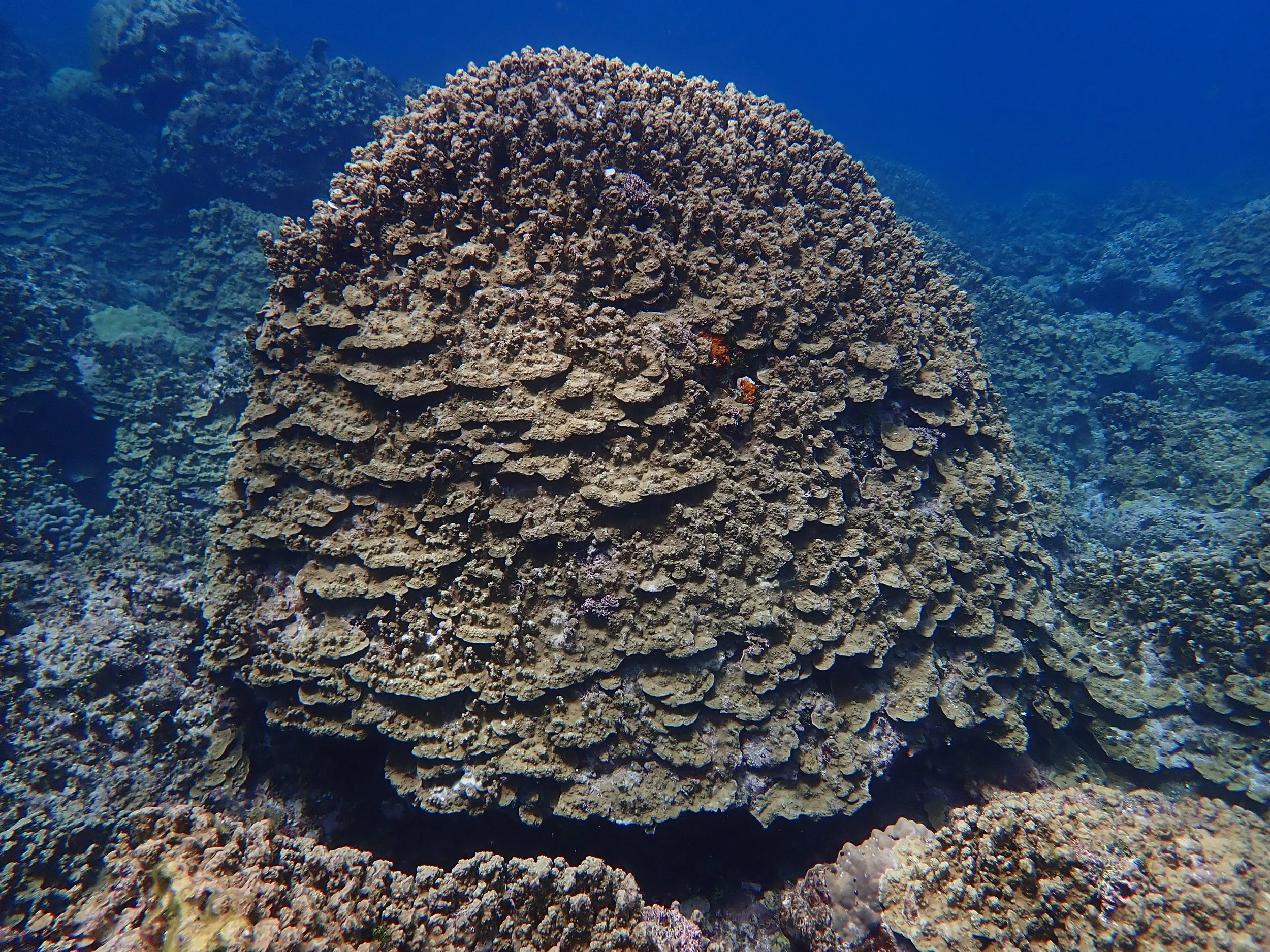

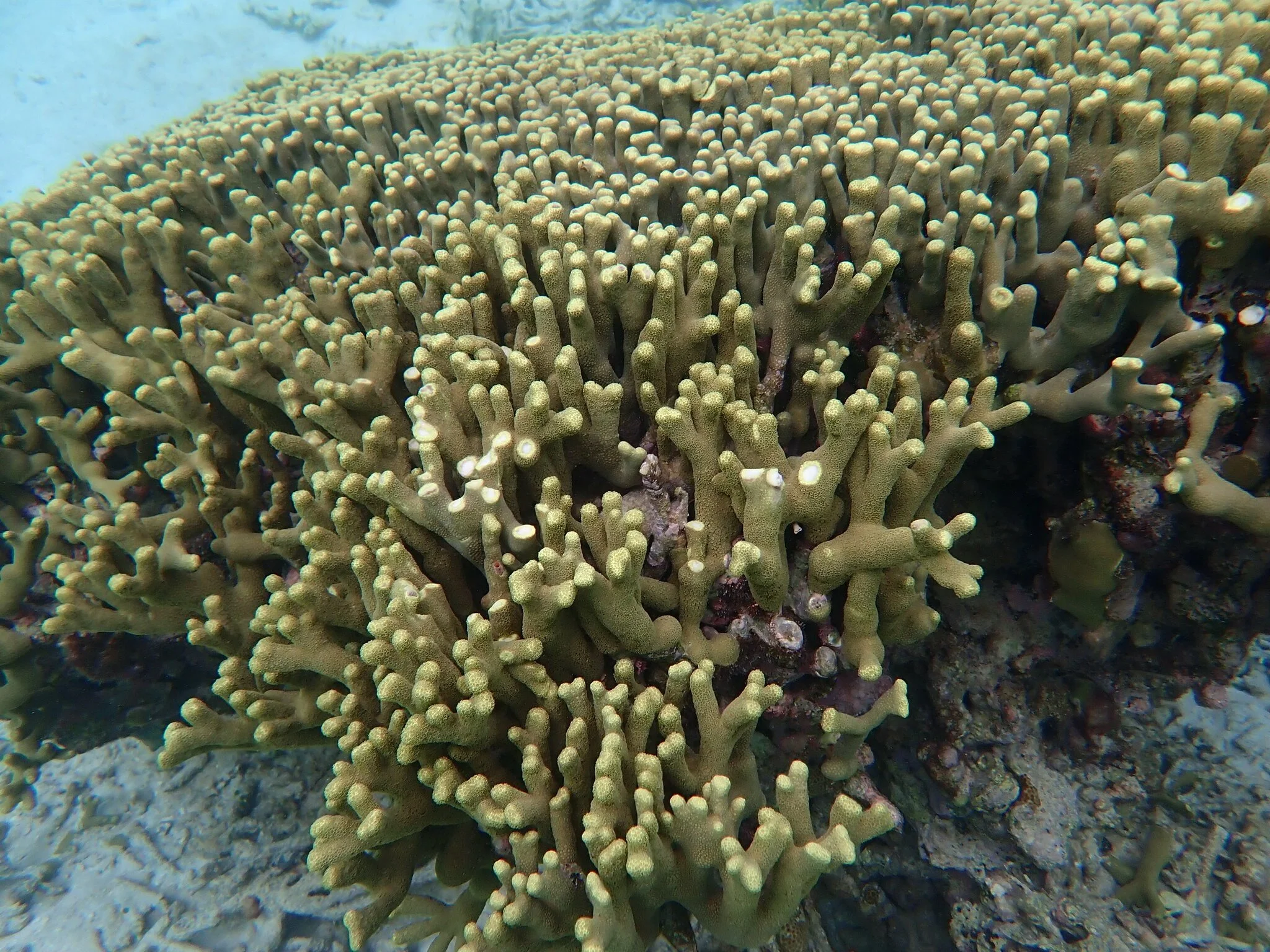

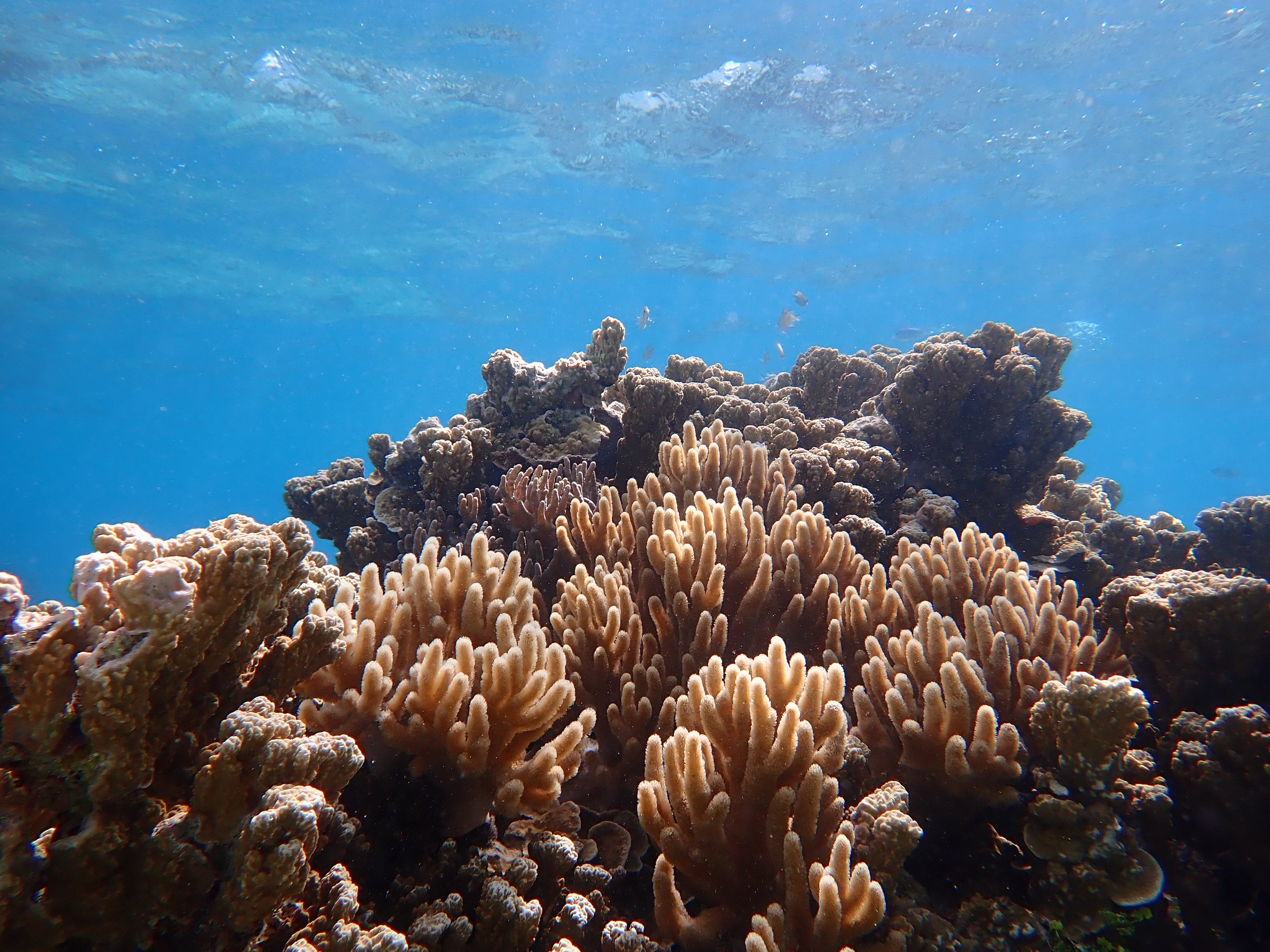

Common corals in Guam

What is coral bleaching?

-

They also give coral their color.

Corals help the zooxanthellae too, by providing a safe place to live and access to sunlight.

This is a symbiotic relationship: both help each other and rely on each other to survive.

-

For example, when the water gets cloudy from pollution or sediment runoff, zooxanthellae cannot access the sunlight they need to do photosynthesis.

If they can’t do photosynthesis, they can’t make food for the coral.

Then if the coral stops getting the food that it needs from the zooxanthellae, the coral will expel the zooxanthellae from its skin.

-

Important note: bleaching does not mean the coral is dead! After bleaching, coral polyps are still alive but are very vulnerable to other threats.

If the threat causing the bleaching disappears (like if the ocean cools down), then the corals can regain their zooxanthellae and recover.

However, if the threat causing the bleaching persists or if there are repeated bleaching events, this can overwhelm the corals and cause them to die.

How are Guam’s Reefs Doing?

Right now they are doing ok, but could be better

Guam’s reefs experienced severe bleaching in 2013, 2014, 2016, and 2017 and lost approximately one-third of all coral in shallow reefs. This was an unprecedented rate of bleaching at the time and made national headlines

Thankfully, there haven’t been any reports of mass bleaching on Guam’s coral reefs since 2017, giving the reefs a much-needed respite.

However, some of Guam’s reefs are still struggling to bounce back from this catastrophic bleaching.

-

There has been a 24% decline in living coral at reef flat monitoring sites 2009-2022 (Burdick et al., 2023)

A 2023 study estimates that the economic benefit value of Guam’s coral reef ecosystems is between $63.4 and $73.6 million annually (Ocean Associates, Incorporated & Eastern Research Group, Inc., 2023)

Recovery from bleaching

The bleaching from 2013-2017 was island-wide, but not all of Guam’s reefs fared the same. Even within one reef site, shallow reef flats were affected differently than deeper seaward slopes or other reef zones pictured in this diagram.

For this reason, efforts have been taken to survey various reef sites and reef zones to understand the different ways that Guam’s reefs have responded to bleaching.

In general, the trend appears to be that slightly more than half of Guam’s reefs have started recovering but still have not recovered to their pre-bleaching state.

-

Bleaching in 2013, 2014, 2016, and 2017 along with extreme low tides in 2014-2015 led to a 60% decrease in coral cover on shallow seaward slopes on Guam’s eastern coast , and a 34% decrease on Guam’s western coast (Raymundo et al. 2019)

During the 2013 bleaching event, sea surface temperature exceeded average monthly temperatures by 0.5°-1.6°C for four months, and 85% of Guam’s coral species bleached (Raymundo 2016)

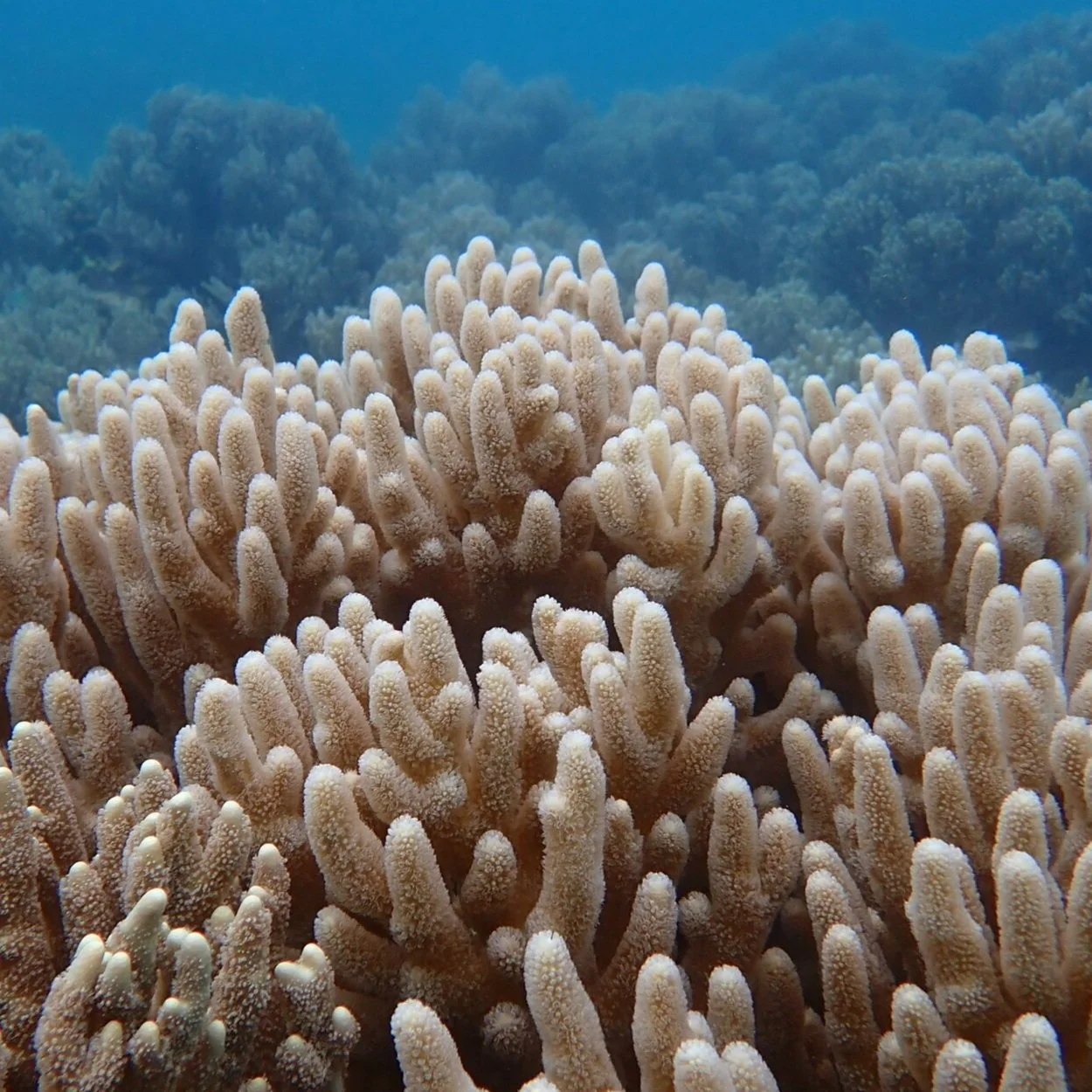

More than half of Guam’s staghorn corals died as a result of coral bleaching events in 2013 and 2014 (Burdick et al., 2023)

-

Ever since the mass bleaching from 2013-2017, coral cover increased in 60% of reef front sites and decreased in 40% of reef front sites through 2021 (Burdick et al., 2023)

Coral cover increased between 2017-2021 at 7 of the 12 sites in various reef zones and decreased at the other 5 sites

Of these 12 sites, 5 of 8 west coast sites saw increases in coral cover, and 2 of 4 east coast sites saw increases in coral cover (Burdick et al., 2023)

Staghorn corals (Genus Acropora) make up a bulk of reef habitats on Guam. However, surveys from 2020 and 2021 suggest that staghorn populations have severely declined and disappeared entirely from 2 sites where they were formerly found in 2017 (Burdick et al., 2023)

Photo from Burdick et al., 2023

Changes in coral communities

Guam is home to hundreds of coral species and some are more resistant to bleaching than others. Over time, repeated severe bleaching can cause tougher coral species to outlast and overgrow the reef while fragile species die off and disappear from the area completely. When this happens, coral cover can remain unchanged but the reef will look completely different.

Surveys and studies show that Guam’s reefs continue to shift towards communities dominated by stress-tolerant coral species, like plate & pillar coral (Porites rus). Meanwhile, Guam’s reefs continue to see declines in stress-susceptible species like staghorn corals (Genus Acropora).

-

While this may sound good to have reefs filled with tough, stress-tolerant corals, the problem is that it lowers the reef’s diversity.

Lower diversity of coral species means that disease and other threats can more easily spread and cause widespread damage.

In addition, losing fragile, stress-susceptible species means losing the food and shelter that they provided for countless marine species.

Each coral plays a unique role on the reef so the benefits they provide to the ecosystem are irreplaceable.

-

There has been a 60% decline in the extent and cover of staghorn coral island-wide 2013-2021

All local staghorn species except for one are now considered uncommon or rare in Guam (Burdick et al., 2023)

Reef-flat monitoring suggests that sites composed primarily of fragile staghorn Acropora corals experienced declines in coral cover of 10-50% between 2009 and 2022 (Burdick et al., 2023)

During the severe bleaching from 2013-2017, reefs on the eastern side of the island suffered a 60% decline, likely because these reefs tend to host more bleaching-susceptible corals (Burdick et al., 2023)

Photo from Burdick et al., 2023

Click the reef sites below to learn more about their recovery and current status

-

Coral cover on shallow reefs has almost fully recovered to its pre-bleaching levels

Pre-bleaching coral cover (2012): 50%

Immediately post-bleaching coral cover (2017): 24%

Recent coral cover (2022): 44%

Coral cover on deeper reefs was moderate and hardly changed at all pre- and post-bleaching

Coral cover remained at ~30% between 2012 and 2020

This lack of change in coral cover is considered to be because this reef is dominated by bleaching-resistant coral species

-

Coral cover on shallow reef flats has recovered to half of its pre-bleaching levels

Pre-bleaching coral cover (2012): 24%

Immediately post-bleaching coral cover (2017): 8%

Recent coral cover (2022): 12%

-

Coral cover on shallow reef flats has recovered and surpassed pre-bleaching levels

Pre-bleaching coral cover (2012): ~32%

Immediately post-bleaching coral cover (2017): ~28%

Recent coral cover (2022): ~34%

Coral cover on deeper reefs was low but hardly changed at all pre- and post-bleaching

Coral cover remained at ~16% between 2010-2020

This lack of change in coral cover is considered to be because this reef is mainly dominated by mounding Porites, a bleaching-resistant coral species.

Will Guam’s reefs bleach again?

Unfortunately, with climate change causing oceans all over the world to gradually warm up, the answer is likely yes.

However, we can use tools like NOAA Coral Reef Watch to be alerted when bleaching could happen in the future.

-

Coral bleaching is often caused by warming waters, so Coral Reef Watch uses a satellite to constantly monitor sea surface temperature (SST) around the world. When they detect temperatures higher than normal in our area, they send us an email alert.

These graphs show Guam’s SST that Coral Reef Watch has recorded over time. Colors indicate the severity of the bleaching alert, with darker red indicating the highest temperatures and therefore the highest risk for bleaching.

Coral Reef Watch ocean temperature data for Guam from 2022-2023

Coral Reef Watch ocean temperature data for Guam indicating high temperatures from 2016-2017, which coincided with Guam’s 2013-2017 mass bleaching

Guam’s predicted bleaching threshold:

86° F (30° C)

Once the ocean surface gets this hot, coral is very likely to bleach

Once we receive bleaching alerts, we can prepare to take action

What does taking action look like? Take a look at GCRI’s Coral Bleaching Response Plan to learn more!

Coral bleaching is a major cause for concern, but it’s not the only threat to Guam’s reefs. Read on to learn more about other reef threats.

Coral Reef Threats

Recreational Misuse

Photo by Dave Burdick

Sometimes enjoying the reef can do more harm than good! Coral reefs are fragile and can easily be destroyed if we aren’t careful. Damage can be prevented if locals and tourists alike implement reef-friendly practices.

-

Standing on corals to take a break while snorkeling

Feeding fish

Riding jet skis and boats on shallow coral reefs

Taking shells home from the beach

Wearing sunblock that isn’t reef-safe and leaches toxic chemicals into the water

-

Sunblock that doesn’t contain chemicals that kill corals!

UV filters found in many sunblocks can actually cause corals to be more susceptible to deadly viral infections. Reef-safe mineral sunblocks have none of these coral-killing chemicals and are a much better choice to wear when enjoying the reef! Recent research may also suggest that these chemicals are harmful to humans too.

But be very careful with sunblocks claiming to be “reef-safe”; many of these still include toxic chemicals because “reef-safe” is not a regulated label.

To make sure your sunblock is truly reef-safe, read the active ingredients list:

Coral-killing ingredients: oxybenzone, avobenzone, avobenzine, octinoxate, ethylhexyl methoxycinnamate, homosalate, octisalate, octocrylene, para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), parabens, triclosan, butyloctyl salicylic acid, any form of microplastic beads

Good ingredients: non-nano zinc oxide, non-nano titanium oxide

Check out our reef-safe sunblock guide to learn more!

-

Because they are important homes to other sea creatures!

Hermit crabs, octopuses, and small fish are just a few examples of reef creatures that take advantage of empty shells and use them for shelter.

Even if shells aren’t in the water providing another creature with a cozy home, they are still important because over time they will break down into small bits of sand. Did you know that we are actually in a global sand shortage right now? It’s true, so every bit of sand counts and we can help by leaving things on the beach that will one day become sand like shells, rocks, dead coral, and other natural materials.

It’s always good to look but not take so that someone else walking along the beach can admire and enjoy what you found!

-

In Guam, the growing number of tourists increases the instances of recreational misuse and reef damage. Before the pandemic, recreational misuse was a major cause for concern with 1.6 million tourists visiting the island in 2019. Tourism has dipped significantly due to the pandemic, with only 216,915 tourists arriving in 2022 (Over 216K Recorded in Visitor Arrivals for FY2022 - Guam Visitors Bureau | GVB, 2022). While devastating to the tourism industry and local economy, this did give the coral reefs some respite. Regardless of current visitation rates, it is vitally important that tourists and locals alike are educated on helpful and hurtful habits when enjoying the coral reefs.

-

Coral reefs that are fractured from vessel collisions are more likely to contract coral diseases (Raymundo et al. 2018)

In 2016, tourist exit surveys show that Guam’s reefs saw over 300,000 snorkelers and 100,000 scuba divers (QMark Research. 2016a and b)

A spatial analysis of oceangoers in Tumon Bay showed that as the number of people using the ocean per unit of area increased, so did the prevalence of coral reef damage. (Hoot et al. 2017)

Overfishing

Photo by the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council

Did you know that overfishing is the leading cause of reef decline worldwide? (MacNeil et al. 2015) Fish are essential to the reef and each species plays a unique role. Overfishing and harmful fishing techniques deplete fish populations and upset the balance of predator and prey.

-

Pouring bleach or other chemicals in the water - this poisons corals and other creatures nearby

Using explosives to stun fish - destroys coral colonies, which can take decades and even centuries to regrow

Abandoning fishing nets - tangled species often drown or starve once ensnared in an abandoned net

SCUBA spearfishing - this modern technology gives humans an unfair advantage over fish, making it dangerously easy to target vulnerable species

-

Each species is an important part of the habitat and helps to keep everything in balance!

Parrotfish, surgeonfish, and other herbivorous fish eat the algae that starts to grow on top of the corals or on rocks where baby corals could settle. Too much algae can crowd out the coral and prevent it from growing, so by keeping the algae mowed down, these fish make space for the corals!

Butterflyfish and other corallivorous fish eat coral polyps and can help to keep fast-growing corals from growing out of control and crowding out other slower-growing species. This helps to keep a healthy diversity of coral species on the reef, which helps to support more species. A recent study also shows that the poop of coral-eating fish may help to disperse photosynthetic algae, like zooxanthellae, that corals need to live!

Sharks (yes, sharks are fish too!), barracudas, and other predators eat fish and other species, helping to make sure that prey populations don’t grow out of control.

Cleaner wrasses and other cleaner fish will pick parasites off the skin of other fish, keeping them free of annoying and potentially dangerous pests!

-

Fishing has been a very important part of Guam’s culture for thousands of years and continues to be today. Locally, 30% of residents fish, and 94% of these fishers do so to feed themselves or their families (NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science 2018). Adopting fair fishing practices will ensure that fish populations in Guam will be around for future generations.

A 2019 fish stock assessment found that 4 of 12 economically and culturally important fish species in Guam are experiencing overfishing:

Longface emperor (lililok) - Lethrinus olivaceus

Bluefin trevally (tarakitu) - Caranx melampygus

Blacktail snapper (kaka’ka) - Lutjanus fulvus

Redlip parrotfish (laggua) - Scarus rubroviolaceus

-

Out of 64 countries and territories compared in a meta-analysis, only two had fish biomass low enough to indicate fishery collapse: Papua New Guinea and Guam (MacNeil et al. 2015)

Over the last 20 years, catch data has shown that larger fish species have been replaced by smaller fish species (Houk et al 2018)

Pollution

Pollution can destroy habitats, poison corals, increase their risk for disease, and choke marine species. The source can be close to the ocean like beach litter, boat sewage leaks, and oil spills. Pollution also comes from land-based sources like fertilizers, sediment, and stormwater runoff.

-

Rivers, creeks, and streams lead to the coastline and can easily transport debris and chemicals to the ocean

Rain and runoff can carry soil, sediment, and other pollutants as they flow downhill to the coast

Animals, like birds or stray animals, may carry debris to the coast. If they eat contaminated food or garbage, their feces can also pollute the beach.

Wind can sweep light objects like styrofoam cups down to the coastline

-

It can make the water so cloudy that it chokes out the coral!

More specifically, the cloudy brown water caused by sedimentation, or a sudden inflow of soil/sediment, can make it difficult for species to look for prey, and prevent coral colonies from accessing the sunlight that their algae symbionts need for photosynthesis. Chemical and sediment pollution can further damage reefs by causing harmful algae to suddenly grow out of control, creating a toxic environment.

-

The main pollutants that impact Guam’s reefs are hydrocarbons, microbes, and sediment with sediment being the greatest threat (Burdick et al. 2008). Sedimentation is caused by increased erosion from things like fires, off-roading, grazing of wild pigs and deer, deforestation, and poorly-planned construction projects. Litter is also a big problem in Guam, and many beaches have large amounts of trash and derelict fishing equipment that invariably makes its way into the ocean.

-

Sedimentation from upland erosion is considered one of the greatest threats to Guam’s coral reefs (Burdick et al. 2008)

Guam’s southwestern reefs have less coral cover, fewer fish, and higher turbidity (cloudier water) than other parts of the island, which is suspected to be due to higher sedimentation (Williams et al. 2012)

Invasive and Nuisance Species

Invasive and nuisance species can rapidly grow due to a lack of natural predators or a change in the environment. This can upset the reef’s ecosystem balance. On Guam, the Crown-of-Thorns sea star (COTS), Acanthaster cf. solaris pictured here is a nuisance species that eats coral and can demolish entire reefs.

-

Invasive species are non-native species that were artificially introduced to a new habitat and are able to rapidly grow their populations in the absence of natural predators. Their population grows out of control, out-competing native species for resources and upsetting the balance of predators and prey in the food web.

Nuisance species, on the other hand, are native to the habitat but are able to suddenly grow their populations in response to a change in the environment that makes conditions optimal for their survival. Usually, this change in conditions is caused by humans. An outbreak of a nuisance species can also be triggered by the population decline of their natural predators.

-

In general, not too many species eat COTS because they have long, pointy spines and harbor venom in their skin and internal organs. However, there are a few species native to Guam that are undeterred by these obstacles and will prey on COTS:

Napoleon wrasse (Tangison) - Cheilinus undulatus

Giant triton snail - Charonia tritonis

Titan triggerfish (Pulonon matingin) - Balistoides viridescens

Starry pufferfish - Arothron stellatus

Some of these species have also declined in recent years due to overfishing or overharvesting, making it easier for COTS to survive and rapidly expand their populations.

-

1. DO NOT TOUCH! They have venomous spines that can puncture your skin and cause a very painful sting

2. DO NOT TRY TO KILL THEM OR CUT THEM UP- you may think this would kill them, but it does the opposite; sea stars can actually grow a whole new body from one severed piece, so cutting them up into bits means you just created a ton of new COTS

3. Take note of its location and the number of COTS there are

4. If there is only one: leave it be (probably not an outbreak)

5. If there is more than one: report this to the Eyes of the Reef Marianas website (could be the start of an outbreak)

Click the blue button on the left to fill out a report

When you report a sighting of 2 or more COTS to the Eyes of the Reef website, this information gets into the hands of local reef managers and they are able to respond accordingly. Do not try to kill COTS on your own; leave this up to the trained professionals

-

Outbreaks of Crown-of-thorns stars (COTS), a major nuisance species, have been reported in Guam for decades. In fact, in a major outbreak from 1967-1969, divers reportedly removed close to 900 COTS from Double Reef alone. Throughout the early 2000s, several COTS outbreaks and subsequent coral reef impacts were also recorded. While the causes of these sudden outbreaks are still a subject of research, evidence suggests they are triggered by warming sea surface temperatures and increasing levels of nutrient or sediment runoff. Thankfully, there haven’t been any significant COTS outbreaks in Guam since 2011.

Although Guam has over 100 non-native species dwelling in our waters, none have been officially designated as invasive. This is very fortunate, but invasive species could easily make their way into Guam’s waters from one of the many ships arriving in our busy ports. Species from the boat’s origin can easily adhere themselves to the side of the boat or even get sucked into the ballast water, only to be released into Guam’s waters upon arrival. (Hoot 2017)

-

In Guam, an outbreak of COTS in the early 1970s led to a 50-60% decrease in coral cover.

Coral cover recovered to 60% after 12 years (Colgan 1987)

COTS (A. planci, which is now considered to be A. cf. solaris) typically spawn during a few months out of the year, but females who are ready to spawn have been documented in Guam during all months of the year (Cheney 1974)

Outbreaks of COTS can destroy 90% of live coral on a reef, with the average COTS devouring 54-140 ft^2 per year (Dixon 1996)

Climate Change

Increased water temperatures due to climate change can cause coral bleaching and speed up the spread of coral diseases. Warming waters are especially dangerous to reefs because corals already live in shallow, sunlit waters, which can heat up faster than deeper waters.

-

Lots of things, but mainly an increase in greenhouse gases.

Climate change is caused by an increase in greenhouse gases, like carbon dioxide (CO2), that accumulate in the atmosphere and act like a warm blanket around the planet, trapping heat inside. In the last 150 years, the amount of greenhouse gas in our atmosphere has skyrocketed due to an increase in human activities that release greenhouse gasses, like burning fossil fuels to generate electricity, drive cars, and heat our homes. This heat-trapping ‘blanket’ around our atmosphere has gotten thicker over the years and continues to gradually warm our planet.

-

Climate change has led to stronger, more frequent storms. Storms bring powerful waves that can easily break corals and cause other physical damage. Increased rainfall and subsequent runoff can also pull harmful pollution into the water, where it can poison corals.

The increased amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) released from human activities can disrupt ocean chemistry. When CO2 dissolves into the ocean, it causes a chemical reaction that makes the water more acidic; a process known as ocean acidification. Even a slight increase in the pH (acidity) of the ocean can wear away at hard corals and other mineralized structures, like sea shells. For corals, this can slow growth rates and make their structures more vulnerable to breakage.

Warm water expands, so the increasing ocean temperature is also causing sea levels to rise. With the water hitting higher up on the shore, cliffsides can erode away much faster and sediment can flow into the water more easily. Sedimentation is a big issue for coral reefs as it clouds the water and prevents coral’s symbiotic algae from getting the sunlight they need to do photosynthesis and provide for their coral host.

-

Guam’s coral reefs are suffering the effects of ocean warming due to climate change. Warming waters caused severe bleaching events between 2013 and 2017, causing over ⅓ of Guam’s corals to die (Raymundo et al. 2019). In the 15 years prior, Guam’s reefs had only been minimally impacted by seasonal bleaching. While there hasn’t been any severe, widespread bleaching since 2017, local coral reef managers continue to monitor reefs for warning signs.

Coral reef managers and practitioners continue to work hard to help Guam’s reefs recover from bleaching events and other threats. One way they are doing this is by growing coral fragments in underwater nurseries, and then out-planting those fragments onto the reef once they are big enough.

-

The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere right now is the highest it has been in 15 million years (Bijma et al. 2013)

The number of days that Guam’s coral reefs are exposed to extreme heat stress has risen from 9 days per year from 1982-1981 to 32 days per year from 2007-2016 (Grecni et al. 2020)

Coral reef gallery

Want to learn more?

Click here to check out our coral reef resources!